What is Drag?

We all know Drag Queens via their theatrical personas; they wave a magic wand and turn themselves into the exaggerated feminine.

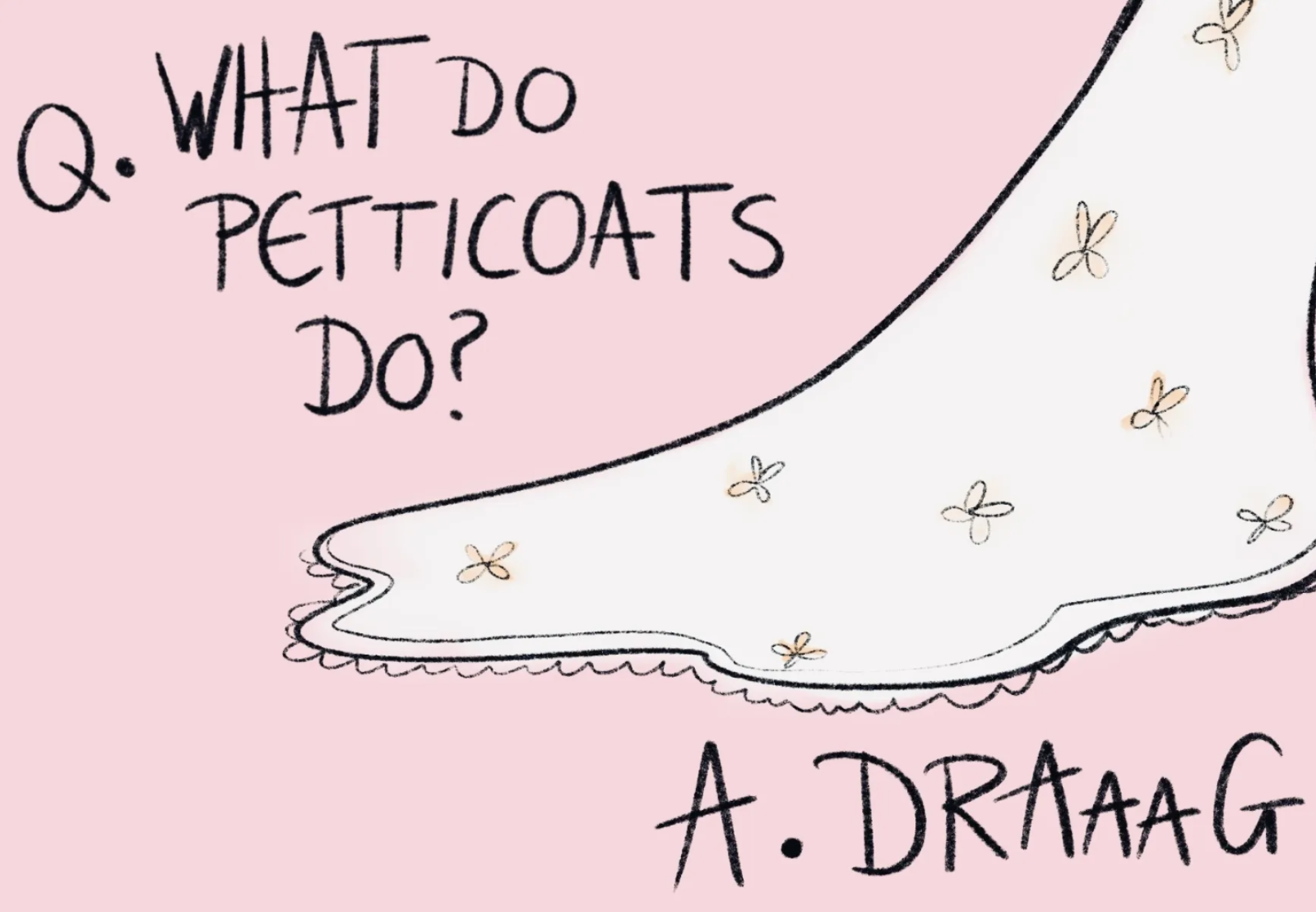

The term ‘Drag Queen’ was born in England — a reference to the way petticoats dragged along the floor when men dressed up in womens’ clothing.

Today, Drag is more commonly associated with the elements of show-bizz, comedy, hen and stag parties, as well as famous programmes such as Ru Pauls Drag Race.

But Drag culture encompasses so much more; it is also freedom, fashion, expression, tranformation, music, celebration, political & performance art, satire, and gender exaggeration.

In essence, drag subculture is the story of those who lie on the outskirts of society. To be accepted meant having to conform. Drag is a story of a power-struggle between LGBTQ individuals and America, written in sequins, crystals, and a sewing needle.

Most modern mainstream names have risen to fame through Drag Race or Netflix’s series Pose. You may have then already heard of Bianca del Rio, Trixie Mattel, Valentina, Violet Chachki, Bianca Castro or Jiggly Caliente etc. These stars represent a rich history and subculture that many are unaware of, but should be.

Lets Start at the beginning: The House of Swann

The dawn of Drag subculture in the Americas was largely led by African-American slaves — in the beginning especially, the exaggerated feminine mimicked ‘the idealisation of white womanhood’, the ‘ideal American Citizen’, or more directly the fashions and habits of plantation owners.

At its core, drag satires its own oppressive forces. For America, Drag began in the 1870s with Willian Dorsey Swann, a queer African-American activist and slave born in 1860.

During the 1880s and 90s when Swann hosted his drag balls in Washington D. C. where fellow Drag Queens and himself would participate in performances such as the ‘cakewalk’. The ‘cakewalk’ was a dance performed by those who had experienced slavery, copying modes of presentation of plantation owners.

Through the 20th century, cakewalking contributed to the rise of what is now widely known today as ‘vogueing’.

‘House Of’

For the earliest non-conformist, black and ethnic Drag Queens of America the subculture was as much a safehaven as it was a mode of rebellion. This was family and a make-shift home which provided shelter from the harsh political landscape of the outside world – hence ‘House of’ and the use of ‘Mother’ as rank title.

Drag has been around since the dawn of human civilization, and many would argue (including myself) that the creative expression of drag is apart of the human condition.

The 80s; Paris Is Burning

Named after Paris Duprees’ annual Drag Ball held in NYC, Jennie Livingstons Paris is Burning orignally aired in 1986. The film follows the experiences of African-American, Latinx, gay, trans, non-conformist individuals. Famously starring Angie Xtravaganza, Kevin Ultra Omnia, and Pepper Labeija as some of its lead speakers. The documentary has since recieved a lot of criticism for obvious reasons despite it highlighting the otherwise underground lives of NYC Drag in the 80s.

It’s newly updated 2019 version, I believe, serves to signal its relevance in today’s culture and politics through re-igniting debates which come with Livingstons work. Calling attention to white neutrality, silencing subaltern voices, and spectaclisation of class struggle through identity.

‘You have three strikes against you; you’re Black, gay and a drag queen.’

Kevin Ultra Omnia famously criticised Livingston for ‘only [showing] the drag queens going on about having nose jobs and snatching burgers, otherwise ignoring contributions made to the Aids epidemic (the political and aesthetic radicalism of Act-Up).

This was seen as reinstating her intention as a white producer making the film for a white audience. Omni’s 2006 follow up in How do I Look opens up a dialogue on the aspects of the performers lives that Livingston left out — the true ambition of education and career — and to re-state the focus of ball culture which is to be free.

Influence

If Drag is seen as a mode of protest against heteronormity, then it needs to be stated that any kind of protest becomes fashionable after a while.

Hence the large amount of Drag subculture that has been appropriated by famous singers, makeup artists, comedians, and large fashion brands.

Makeup

Can’t live without contour or baking in your makeup routine?

You don’t have to look deep into classic Drag makeup styles to find the route inspiration of popular trends like bold eyes, exaggerated winged liner and perfected larger-than-life hair. Not only have visual aesthetics been influenced but also method of application.

It’s no easy feat working under hot stage lights for hours whilst looking flawless. Thank Drag, our Queens brought the fool-proof methods of contour and baking for a snatched, perfected look to mainsteam society. I was personally introduced through Youtube channels, however, Queens have been collaborating with makeup and fasion companies since the 90s. Numerous Drag Queens have since naturally developed their own bulletproof beauty brands like Trixie Cosmetics and BOMO Beauty.

In Vogue

By the 90s, Drag Queens were beginning to grace the mainstream stage with their presence; walking runways, hosting shows, and collaborating with celebrities like Madonna.

Vogue, Madonnas 1990s hit song directly takes from Harlems Ballroom culture of vogueing (dance style inspired by fasion model posing). Her introduction to the Drag subculture of Harlem began when she left her hometown in Michigan for the Big Apple with $35 to her name and a dream. It was individuals from the House of Xtravaganza that taught her to vogue. The choreography for the black and white music video was choreographed by said Harlem Ballroom members, Luis Camacho and Jose Gutierez Xtravaganza.

The relationship between celebrities and their queer inspiration will largely remain complicated as it is not unusual for members of the LGBTQ+ community to feel both empowered yet ripped-off by some super stars who appropriate fashion, makeup, and dance from Drag subculture.

Fantasy

Fantasy, although an important element of ball culture, does not in fact describe its legacy. Drags’ legacy also describes a journey towards American citizenship, the representation of restriction in traditional labels, as well as acceptance of those who do not fit under these ‘traditional labels’.

Just like Swanns’ ‘cakewalking’, new categories of dress in ballroom culture continue to develop and describe the boundaries between race and gender withing the postcolonial world.

These categories are mostly based on white symbols of success which present ‘(whiteness) itself as the only meaningful life there is’, as Bell Hooks writes in Black Looks: Race and Representation on the film.

Drag Queens transmute their own oppression into a modes of performance art like comedy, dance & music, and fasion, flipping gender expectation by fusing mainstream personas with personal sensuality.

What RuPauls Drag Race and Pose did successfully (which other docuseries and programmes have failed to do) is present Drag Queens as whole, rounded people, including stories of their personal struggles outside of ballroom and show-bizz culture.

I first discovered the world of Drag in 2012. I was 11 going on 12 at the time, and coming from a rural community in Wales, United Kingdom, it was a colourful revelation. Drag, its history, culture, and icons have captured my imagination (like many others) and inspired my own work since (like many others).

Written by Shona Gracie Cugat-Davies